|

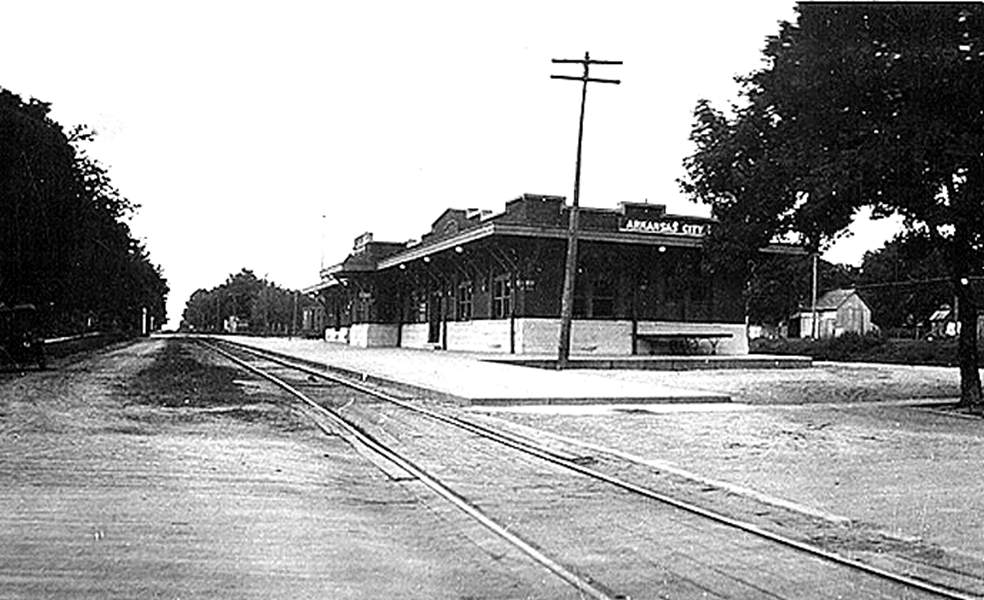

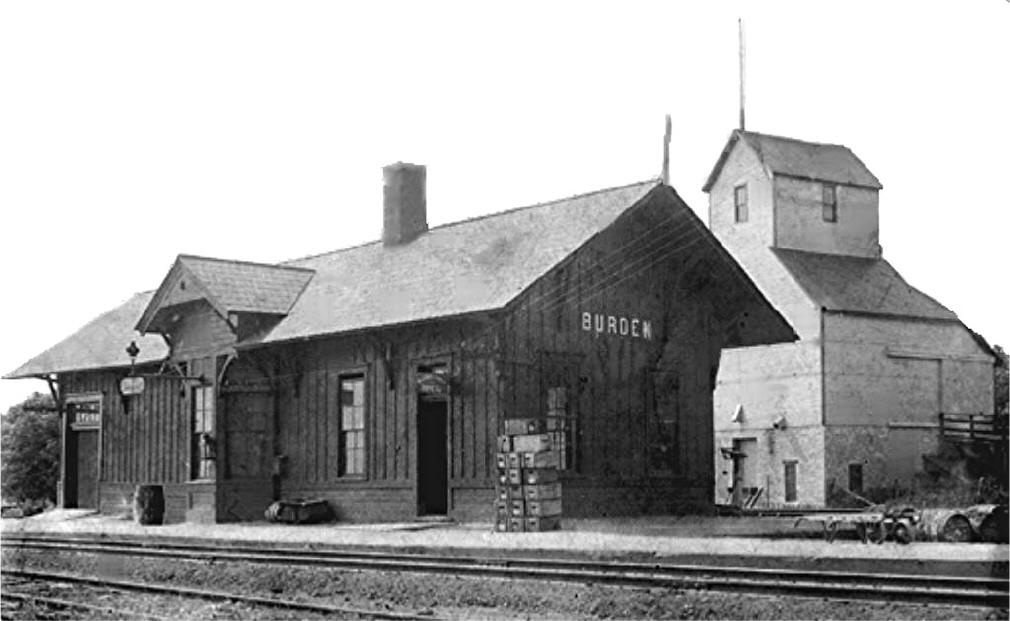

Rail Roads of Cowley County |

|

|

Moving Train Engine to Wilson Park |

|

| By FOSS FARRAR | |

| Traveler Staff Reporter | |

| reporter@arkcity.net | |

.jpeg) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

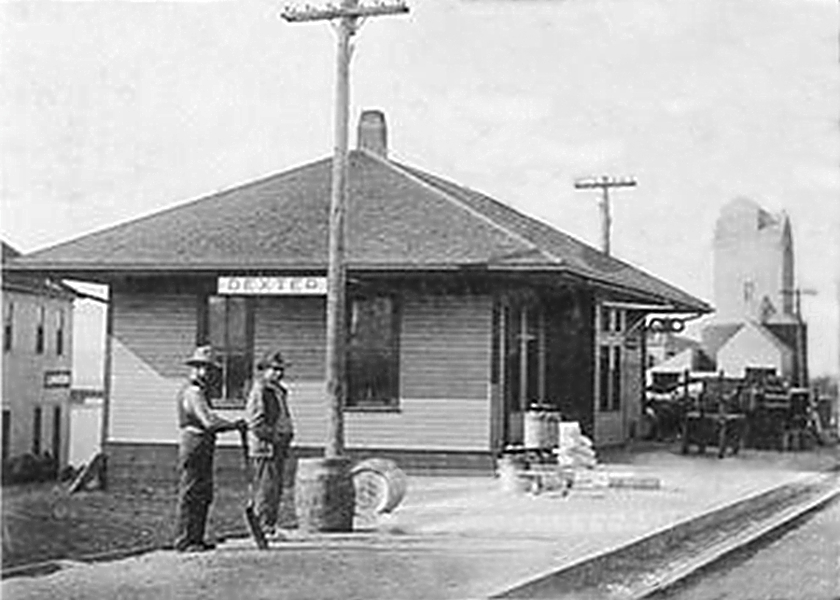

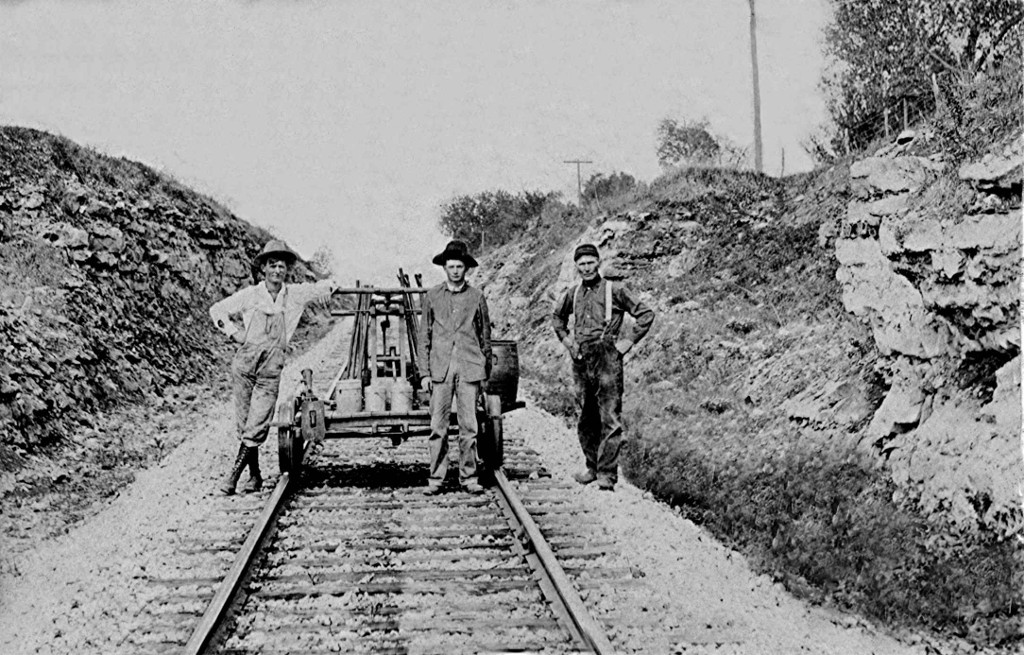

Dexter Ks. |

|

|

|

|

|

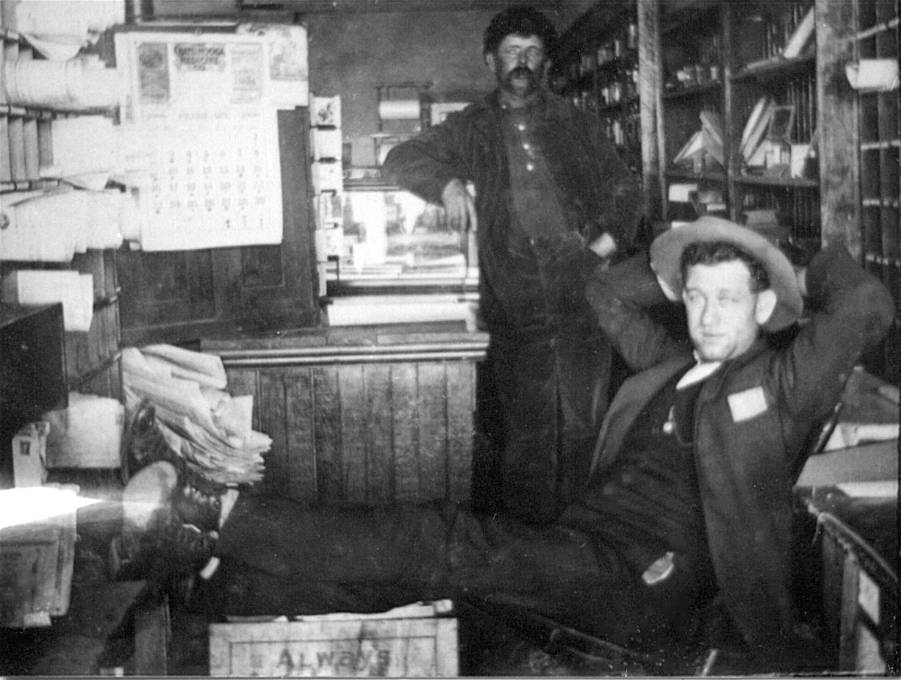

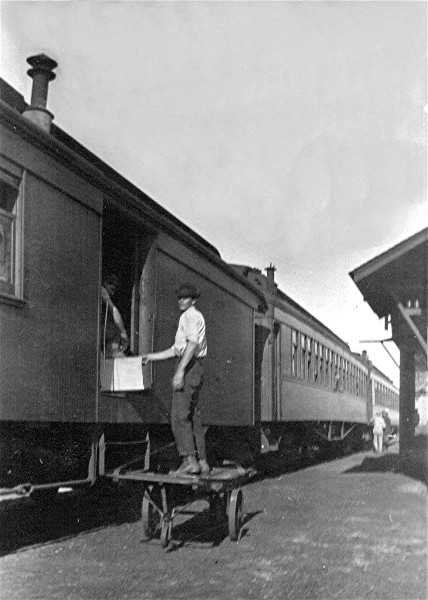

Can you name any of the Arkansas City crew?? |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

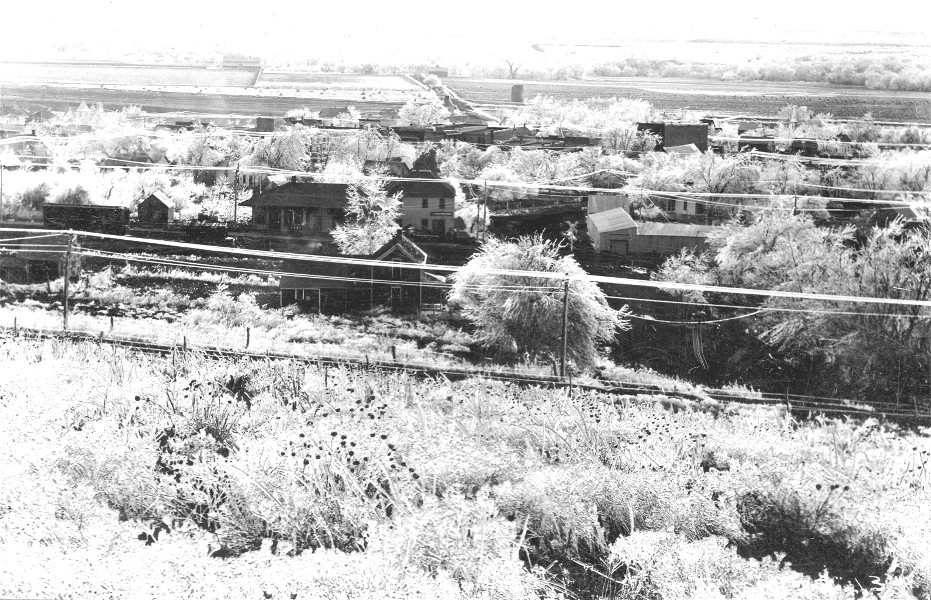

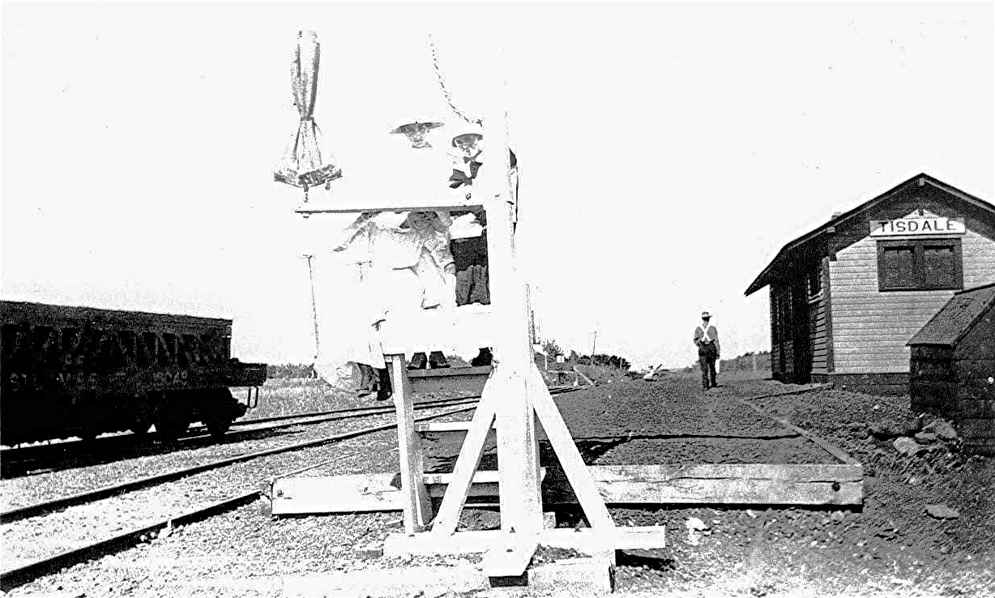

A VIEW OF A VANISHING TRAIL |

|

|

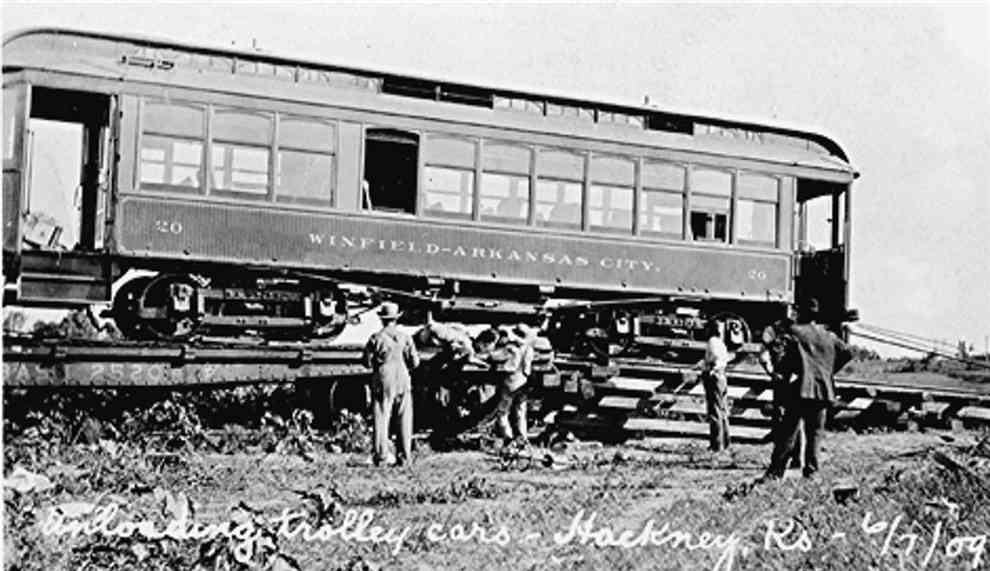

LAST TRIP OF MULE CAR TO COLLEGE HILL |

|

|

XXX 6th 1909 WINFIELD, KS |

|

|

This was taken off the above picture |

|

|

James A. Selan Santa Fe Railroad Employee 1905 - 1956 |

|

|

by Joline (Selan) Iverson August 20 2007

|

|

Jo Burke - Brakeman, James (Jim) Selan Conductor by his Waycar, Unknown |

|

|

|

|

|

Santa Fe Railroad - James and Swan Selan |

|

|

|

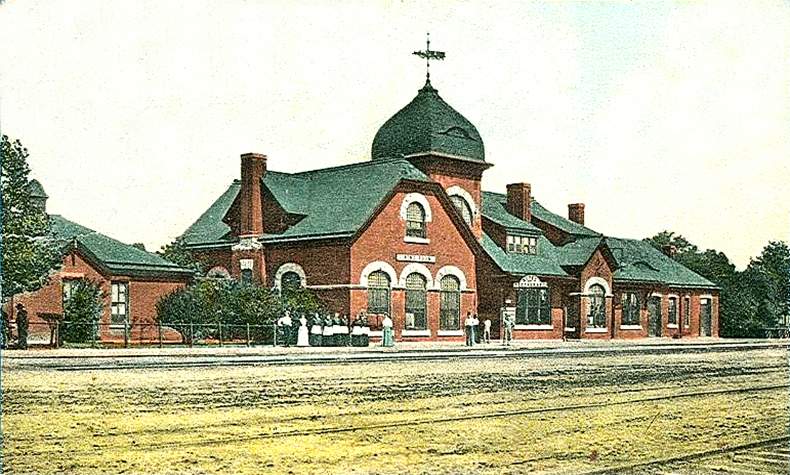

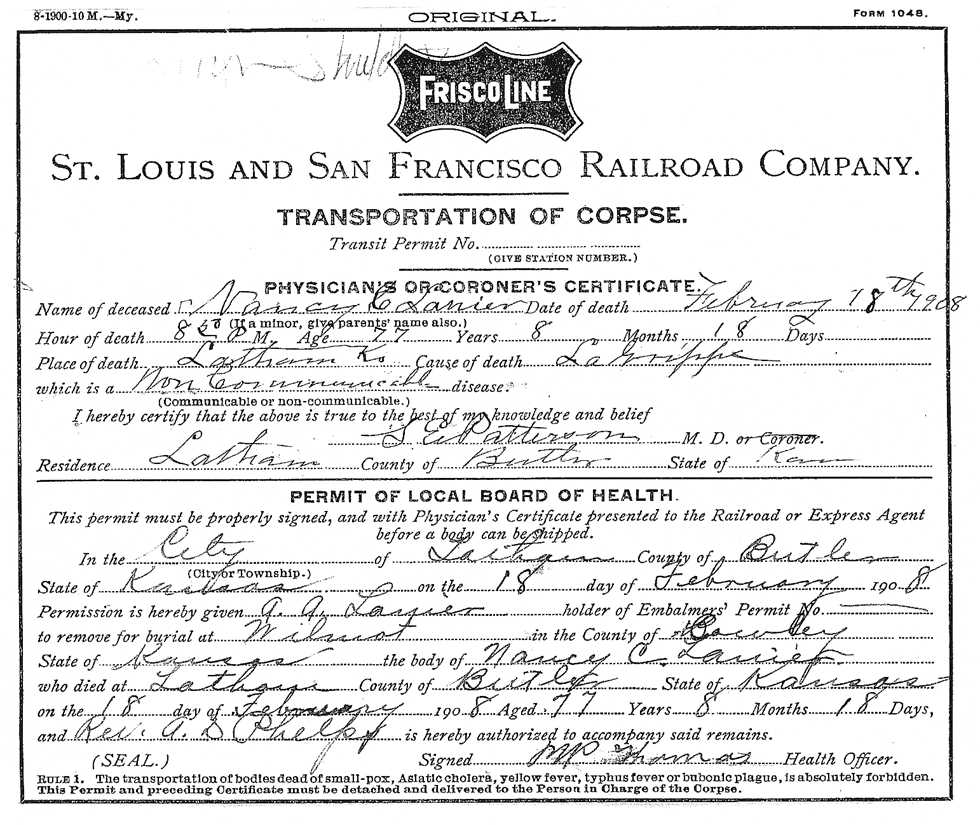

Around 1900, two young men living in Omskoldsvik, Sweden decided to come to America to seek their fortune. The first one to immigrate to America was the older brother, Sven Selander. I never found out how he arrived and how he stayed in Arkansas City, Kansas, but he did stay and began working for the Santa Fe Railroad. Jonas Alfred Selander, d.o.b. November 14, 1887, the younger of the two, came over around 1905. He passed through ElIis Island and since Swan had dropped the d e r from his name then Jonas Alfred Selander became James Alfred Selan (or Jim). The two brothers had never been close but Jim did come to Arkansas City where his brother Swan was living and working. Jim had heard that the villains in America were men, wore black, and had black mustaches. So here he came a young man not able to speak one word of English. Jim began getting off of the train with his accordion under one arm and carrying a small straw valise with all his worldly possessions inside with the other hand. Here came the baggage man to help him get off. Yes he was a man, dressed in a black uniform and also had a black mustache. Jim thought he was trying to steal his accordion and his valise and began shoving the baggage man. Jim also began to cry as he did not understand a word of English that was being said to him. Several people and workmen began gathering around because of the commotion. At first they thought he was a German boy. Several of them ran over to the Santa Fe office building which was to the North of the depot to get a gentlemen with the last name of Holm stein. Mr. Holmstein came over to Jim and found out that Jim was Swedish and so was Mr. Holmstein. A friendship began. Mr. Holmstein found Jim a room to rent which included meals but bigger still gave Jim a job at the Santa Fe Material Yard which was at the corner of Mill Road and Chestnut Avenue ($13 a week). The Material Yard was a hot and difficult job handling the creosote covered ties and everything it took to maintain the train tracks. Since Jim did not understand English he also did not understand what the noon whistle meant so he would keep working. There were a lot of incidences that were funny to other men but I am also sure that Jim had to bear the brunt of these jokes. Jim worked in the Material Yard until he could write and speak English. At this time he went to the Santa Fe office and talked to Mr. Holmstein about taking tests to be a brakeman which was the operating part of the railroad. WW I was brewing in Europe and the railroad knew that it would spill over to the United States. Mr. Holmstein said that there had to be people to run the railroad while a lot of the men went into the service. Jim then studied the manual, took the test and passed to become a brakeman. Jim stayed here as did his brother, Swan, and worked operating the trains during WW I. Jim was a brakeman for many years and then moved on up to be a conductor. Swan was made an engineer. He had been a fireman. Men who have worked on trains that just happened to have both brothers on it said Swan always told Jim that he was "the boss because he drove the train". In October of 1930, Jim married Alyce LaMotte Barnett, and so Jim became my stepfather. (I was five years old.) He was very good to me and the only Dad I ever knew. He and my mother, Alyce Barnett, met at the Harvey House which was in the old depot. She had been widowed at twenty and with me a baby of eight months old. Alyce had looked for work and finally found a job at the Harvey House. I assume as a Harvey Girl because of her uniform. This was in 1926. The unmarried Harvey girls lived upstairs over the depot and no one was allowed upstairs in their quarters, but mother lived at home with me and her parents. Jim did not talk a lot but I do recollect hearing him tell about walking on top of the freight train while it was moving. He fell off and only received scrapes and bruises. I also would hear him talk about his lantern. There were so many signals that they could almost talk with their lanterns. This was good as they didn't have radios or any kind of intercom system from the way car (caboose) to the engine like they do today. There were many stories some I can't remember now but there was one that I have always enjoyed. It was early 20's or late 1900's when the Lindsborg College Choir was going to Oklahoma City to sing the Messiah. Jim was the conductor and went back to the choir's car. In Swedish the choir was griping about Jim being back in their car and Jim listened. Finally, he grinned at them and in Swedish explained his duties. The choir was very surprised. They had a good laugh and gave him a ticket to the concert. Another story my mother liked was when Jim was conductor on a special cattle train during the cattle rush (I might say now that Jim liked freight trains much better than passenger trains. He said it was too hard to get the people rounded up to punch their tickets.). Jim went back near one of the cattle cars and there sat a man that looked like a bum. Jim was nice to him and it turned out that all of their cattle were owned by this "bum" and it was his practice to ride from South Texas up to the Flint Hills with the cattle. Every year after that we would receive 50 lbs, or a large gunny sack, of pecans picked from his trees. They were fresh and my mother enjoyed baking with them. By the way, at this time with the old steam engine there was quite a crew on the freight trains. There was the engineer, fireman, brakeman, rear brakeman and conductor. The rear brakeman and conductor were almost always in the way car or caboose. In the late 30's and 40's during WW II on top of the number of crewmen there was also a fifty car limit for each train. So there were many, many crews and many, trains that were running out of Arkansas City. This was also a very busy time with extra boxcars waiting on the sidetracks. There was the wheat rush, cattle rush and many work trains besides other freight trains. To my recollection there were probably four passenger trains going each direction each direction through Arkansas City. There were also a lot of different jobs that the Santa Fe offered such as car men, switch engineers, and all kinds of workmen right in the depot (Incidentally, my husband's father was a car man with the Great Northern Railroad in St. Paul, Minnesota). There were also different divisions back in those days. There was the Eastern, Middle, Oklahoma (that's where Ark City was), and Southern. That shows you what a very large industry the railroad was for Ark City and I have probably forgotten many other men and jobs since it has been so long ago. I'll quickly mention in conclusion what being a railroad family meant to me. It was really a good life. We had everything we needed. The city depended on the railroad because of the Shell Refinery and many other business closings because of the depression. My dad loved the railroad and his waycar or caboose was his home away from home. He never stayed in hotels at the other end of the line. He had food for his needs and they used to kid him and say he had everything in his caboose but lace curtains. There was only one thing wrong with a man who loved his work too much. Our two weeks vacation was spent in Chicago, always. We left on the 15th of August unless Dad was on call. If he was, we had to wait and never, never did we leave early. We would then leave on number 5 or 6 which left about four in the afternoon and arrived in Chicago the next day about 9 in the morning. I think I can remember the smells and the noises and the wonderful fun that we all had on the train. I always wanted to eat in the dining room but it was very expensive by the standards of the time. So, we had the best ham sandwiches that were sold by a vendor who ,went through the car. It was just a wonderful fun time of my life. I took many, many trips before I was married since Dad worked for the railroad. I went all over the United States on passes both from the Santa Fe and foreign railroads. During the best years of my life, Alyce and Jim (Mom and Dad) blessed me with two brothers, James Jr. and Jack. James was seven years younger than I was and Jack was thirteen years younger. They just added more love and fun to my life. There are a lot of stories that have been told about the two Swede brothers Jim and Swan. I wish I knew them all. I also wish that everyone had the opportunity to ride trains the way that I did. I could go on and on about the many adventures that the railroad offered to me and to others at that time in history. James Alfred (Jim) Selan died in his sleep in October 18th, 1956, after working over 50 years for the Santa Fe Railroad. |

.jpg)